Germanic Tribes

The Ancient Germans remained near the Urheimat though considerably expanded their territory. Nowadays there are almost ten Germanic languages divided into three groups. Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic and Faroese belong to the northern group. English, German, Dutch and Frisian compose the western group. The extinct languages (Gothic, and that spoken by the Burgundians, Vandals, Gepids, and Ruguans belong to the eastern group. But according to F. Maurer, the Germanic tribes were initially separated into five groups: the Northern Germans (ancestry of the present-day Danes, Swedes, Norwegians, Icelanders); the Eastern Germans (Goths, Vandals, etc); the Elbe Germans (forebears of modern the Germans, i.e. Semnons, Suebs, Quads, Markomans, Hermundurs, Longobards etc); the Rhine-Weser Germans (ancestors of modern Dutches and Flemish); the North Sea Germans (Anglo-Saxons and Frisians)(SCHMIDT WILHELM. 1976: 45). It is supposed that common language for all Germanic tribes existed till the 3rd c. AD and it was split after the migration of Germans into the Central and North Europe (Ibid:44). But the analysis of Germanic languages by the graphic-analytical method brings us to absolutely different conclusions.

| Languages | German | English | Netherl | Northern | Gothic | Frisian |

| German | 884 | |||||

| English | 601 | 858 | ||||

| Netherl | 503 | 357 | 632 | |||

| Northern | 412 | 468 | 226 | 651 | ||

| Gothic | 228 | 205 | 132 | 166 | 305 | |

| Frisian | 248 | 237 | 245 | 128 | 82 | 329 |

Left: Table 7. Quantity of mutual words in pairs of Germanic languages

According to the primary split of the Germanic languages, such languages were taken to the research – English, German, Netherlandish (Dutch-Flemish), North Germanic group and Gothic. Frisian language was added to the study later, but as it appeared, it cannot be inserted into a common model of Germanic language relation. Obviously, the Frisian was formed at some later time. The table-dictionary of Germanic languages was composed by using the data from the etymological dictionaries of German (KLUGE FRIEDRICH. 1989), Gothic (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1934), Old English (HOLTHAUSEN F. 1974), North Germanic (KÖBLER H. 2003), and Dutch (van VEEN P.A.E. en van der SIJS NICOLINE.1989), and also bilingual dictionaries. In total 2628 phono-semantic sets were analyzed. 1424 of them were admitted as common Germanic words. The number of mutual words in the language pairs is presented in table 7.

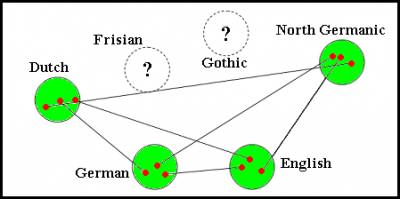

Using these data, the model of the relation of the Germanic languages except Frisian was built quite easily (see figure below)

After repeated additions to the Table-dictionary of the Germanic languages, the scheme of kinship was not changed. The location of the English, German, Dutch and North Germanic language was always the same but reliable placement of the Gothic language was not succeeded because of insufficient data. Introducing Frisian to the scheme didn't significantly help to resolve the situation.

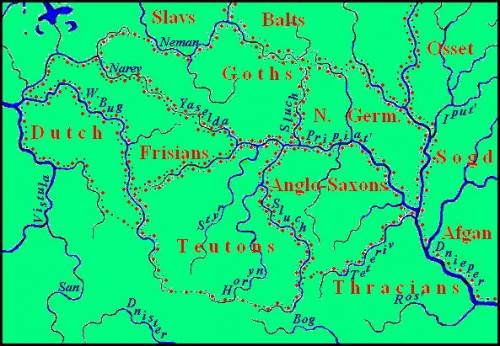

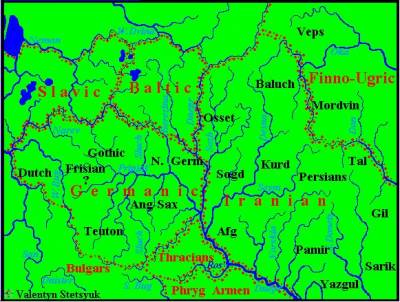

Since we have only four reliable nodes of graph, it is very difficult to find a proper location for the model on the map – a variety oh locations are possible as the total number of languages is relatively small. A found position will be more veritable if it will be confirmed by other facts. Let us admit such location of the model that the area of Anglo-Saxons lie upon the Urheimat of Italics between the Teterev, Pripyat’ and Sluch (rt of the Pripyat') rivers. In that case, the area of the ancestry of modern-day Germans (let us name them for convenience Teutons) can be located on the former area of the Illyrians on the Sluch, West Bug and Pripyat’ basins. The former area of the Celts on the both sides of the West Bug is due to the ancestors of modern Dutch. Accordingly, North Germanic speakers (the ancestors of Swedes, Danes , Norwegians , Icelanders) had to take the area of Greeks between the rivers Pripyat, Dnieper and Berezina. In such a case only one area between the upper Pripyat and Neman from the Yaselda till the Sluch (lt of the Pripyat) remains for the Gothic and the Frisian languages. The location here the Urheimat of the Goths, Vandals, and Burgundians contraries to an insufficient number of common words between the Dutch and the Gothic language. This makes us believe that these old Germanic tribes could nor be the neighbors of the ancestors of the Dutch. Between their areas had to be located another tribe. Perhaps it was the ancestors of the Frisians. The number of common words between the Frisian and other Germanic languages do not contradict this hypothesis. In this situation, the problem might be solved so that the ancestors of the Dutch occupied territory not on both sides of the Western Bug, but only of its left bank and the right bank should have been settled by the Friesians. Then common Germanic territory could be presented as on the map ebove.

Since we have only four reliable nodes of graph, it is very difficult to find a proper location for the model on the map – a variety oh locations are possible as the total number of languages is relatively small. A found position will be more veritable if it will be confirmed by other facts. Let us admit such location of the model that the area of Anglo-Saxons lie upon the Urheimat of Italics between the Teterev, Pripyat’ and Sluch (rt of the Pripyat') rivers. In that case, the area of the ancestry of modern-day Germans (let us name them for convenience Teutons) can be located on the former area of the Illyrians on the Sluch, West Bug and Pripyat’ basins. The former area of the Celts on the both sides of the West Bug is due to the ancestors of modern Dutch. Accordingly, North Germanic speakers (the ancestors of Swedes, Danes , Norwegians , Icelanders) had to take the area of Greeks between the rivers Pripyat, Dnieper and Berezina. In such a case only one area between the upper Pripyat and Neman from the Yaselda till the Sluch (lt of the Pripyat) remains for the Gothic and the Frisian languages. The location here the Urheimat of the Goths, Vandals, and Burgundians contraries to an insufficient number of common words between the Dutch and the Gothic language. This makes us believe that these old Germanic tribes could nor be the neighbors of the ancestors of the Dutch. Between their areas had to be located another tribe. Perhaps it was the ancestors of the Frisians. The number of common words between the Frisian and other Germanic languages do not contradict this hypothesis. In this situation, the problem might be solved so that the ancestors of the Dutch occupied territory not on both sides of the Western Bug, but only of its left bank and the right bank should have been settled by the Friesians. Then common Germanic territory could be presented as on the map ebove.

The Map of the Germanic and Iranian habitats.

Legend: Afg – Afghani, Gil – Gilanian, Pamir – Pers – Persian, Yagn – Yaghnobi, Yazg – Yazgulami.

Legend: Afg – Afghani, Gil – Gilanian, Pamir – Pers – Persian, Yagn – Yaghnobi, Yazg – Yazgulami.

There is historical evidence of the presence of the Germans on the territory of the Ukraine, referring to the time when they have not to be presen there, but their name was transferred to the Slavs, who settled on the old German Länder. In 970 the Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimisces (969 -976) reported the Kiev prince Svyatoslav (964 – 972) through the Ambassadors message, which consisted of the following words:

I believe that you have not forgotten about the defeat of your father Ingor, who despised the oath sailed to the capital of a huge army of 10 thousand ships, but to the Cimmerian Bosporus arrived barely a dozen boats, beeng himself a messenger of his troubles. I do not mention nothing about his [further] miserable fate, when, having gone on a campaign against the Germans, he was taken captive, tied to a tree trunk and broken in half (Leo the Deacon, 1988, VI, 10).

It is clear that we are talking about Prince Igor, martyred at the hands of the Drevlyan inhabiting the Anglo-Saxon area at that time. As we shall see later, there is evidence that the Anglo-Saxons remained on the Ukrainian territory until the "Great Migration." In this regard, the origin of the ethnonym Drevlyan "can be output from the name of a well-known Germanic tribe Turvin (Yaylenko VP, 1990, 116). Tthe tribe Drevlyan belonged to the ancient Rus’ state long time. They were not included in it at leat in the10 century, as repeatedly stressed in his work, A.N. Nasonov (Nasonov A.N, 1951, 29, 41, 55-56). The fact that the Vikings could not include in the "Russian land" adjacent to the Polans the Drevlyans can say that these were the remains of their relatives Anglo-Saxons, mixed with the alien Slavic population. The chronicle notes that the custom of the Polans was "meek and quiet", whereas Drevlyans "lived bestial way", ie they were more belligerent or unruly.

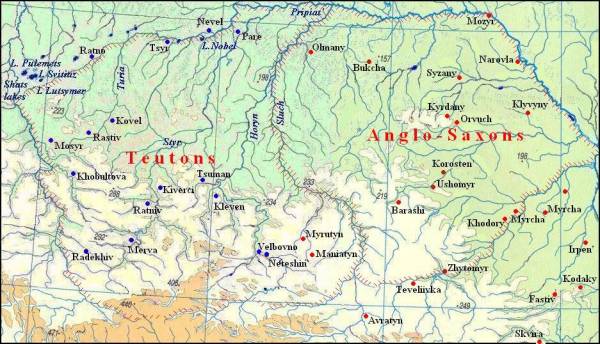

The presence of Germanic tribes on the determined by us area can be also confirmed by the remnants of the German and English place names in those habitats that have been identified as the Urheimats of the ancestors of Germans (we call them the Teutons) and the Anglo-Saxons. The determined territory coincides to a great extent with the region of Třynec culture of uncertain origin which existed from the second quarter till the end of the 1st mill BC. Thus, this culture can be plausible considered as of Germanic origin. Such assumption may be confirmed by connections of discrete Germanic languages with the Iranians, since the Iranian areas were located near-by on the Dnepr's left banks. The made comparative analysis of table-dictionaries of Germanic and Iranian languages discovered 253 Germanic-Iranian lexical correspondences. The North Germanic languages have at most Germanic-Iranian matches, namely 193 ones. The English has a bit less, 173 matches, but German has considerable lesser, only 95 ones. The Ossetic language has mostly Germanic matches, to wit 143 ones. Pashto and Kurdish have 93 matches, Yaghnobi has 67 ones etc.

These data can confirm that the North Germanic and Ossetic areas were once adjacent. The availability of numerous Germanisms in Ossetic has been known long ago, but linguists neglect the fact that Ossetic has the biggest volume of matches just with the North Germanic languages. The area of initial formation of Proto-English was near-by to the Yaghnobi and Pashto areas, therefore English should also have many common language connections with Pashto and Yaghnobi, but connections of Germanic languages with these Iranian languages are perhaps yet to be investigated. Detailed study of these connections can provide linguists with rich material for the further research. The Yaghnobi vocabulary is scanty represented in the table-dictionary because the lexical material of this language was taken from an available small dictionary. Nevertheless, interesting examples of the isolated matches of this language with the North Germanic languages and English one were discovered:

Eng. bug – Yagn. bugalak “gadfly”;

Eng. cog – Yagn. ozax “tooth”;

Eng. jump – Yagn. jumb “to move”;

Eng. moth, Swed. mott, Ger. Motte – Yagn. mоtta “bread moth”;

Swed. digna “to fall”, dingla “to hang over”– Yagn. dangal “fell”;

Swed. mögel “mould” – Yagn. magor “mould”;

Swed. sarg “edge” – Yagn. sarak “edge”.

The Pashto area was located as nearest to the English one and this was resulted in such English-Pashto matches:

O.E. beam “a tree’, Eng beam – Pashto bəna “a tree”;

Eng dapper – Pashto debər “stout, fat”;

O.E. fright, Eng right – Pashto rixtija “truth, verity”;

O.E. gæt “opening, passage”, Eng gate – Pashto get. “gate” (modern loan-word?);

O.E. lyft “weak, foolish”, Eng left – Pashto lavt “weak”;

Anglo-Saxon minnia “love” – Pashto mina “love”;

Eng. mitt “hand” – Pashto met “hand”(modern?) ;

Eng. to rate “to scold” – Pashto ratəl “to scold”;

O.E. scīr, Got skiers and others Germanic “clean”- Pashto x.kāra “clear”;

Eng. to search – Pashto surag’ “to search”, Pers. sorag’ “to search”;

O.E. spearca, Eng spark – Pashto speregej “spark”;

O.E. sprot, sprota, Eng sprout – Pashto – spartak “twig, vine”;

O.E. wadan “to go forward”, Eng wade – Pashto wāte “going put”;

O.E. weddian “to pledge, marry”, Eng to wed, wedding – Pashto wāde “wedding”;

O.E. wherry (boat) – Pashto berej “raft”.

The presence of Germanic tribes on the determined by us area can be also confirmed by the remnants of the German and English place names in those habitats that have been identified as the Urheimats of the Teutons and the Anglo-Saxons (see the map above).

However Pashto has many English loan-words of modern days, such as Pashto bench (Eng bench), Pashto strābari (Eng strawberry) etc, therefore it is very difficult to separate common ancient lexical heritage from nowadays borrowings. Some lexical coincidences can have common origin from Greek or Latin. One must say that English-Iaranian connections are not yet studied sufficiently. For example, Eng. hog is supposed to be of Celtic origin but it has many matches in the Iranian languages, which are unknown (Yagn, Afg xug, Shung xūg, Gil xuk, Pers. xūk, Yazg. xəg etc) for scholars. Many Germanic words have Iranian matches (Ger Damm, Sw damm “dam”, Ger Faß ‘barrel”, Haus “house”, Hammel “lamb”, Rain “border”, Reif “rope”, waten “to wade”, Zagel, Sw tagel “tail”) but it is vainly to look for them in the Etymological Dictionary of German Languge

At left: Germanic and Iranian habitats.

Legend: Afg – Afghani, Gil – Gilanian, Pamir – Pers – Persian, Yagn – Yaghnobi, Yazg – Yazgulami.

Besides, there are such Germanic-Iranian parallels which connection is not clear. For example, Ger Bast, Eng, Dutch, Ic bast corresponds with the word bast “to join” which is present in many Iranian languages, Ger Hirse, OS hersija “millet” can be connected with Kurd herzin, Tal arzyn, Pers ärzan “millet”. Bur the most interesting example is such Germanic-Ossetic parallel: Ger Farbe, Dutch verv “paint”, Sw färg “colour”, Got farwa “deportment, carriage”. One cannot at once to find a match in English fallow. All these words can be united by Os färw “alder-tree” which has no Iranian parallels. It is known that the bark of this tree can be used for painting and gives red-yellow or brown-yellow colour. Maybe Ger Falbe “a dun, light-bay horse” belongs to this word group. V.I. Abaev considered the Ossetic word as a loan-word from O.U.G fеlawa “willow-tree”. In such case, Slav. vьrba, Lit virbas “vine”, Lat verbena have to be joined here too. Ger Falbe is connected by Kluge with Gmc *falwa “light-yellow” parent Slav. *polvь, Lit palwas.

As we can see on the map 5, the forefathers of Albanians, the Thracians were the nearest neighbours of Germanic tribes on the southeast. The Pashto Urheimat was located over the Dnepr. All these languages can have common lexical heritage. However the Germanic-Thracian language connections are researched insufficient, to say nothing about Pashto-Albanian ones. Brief survey of the vocabularies of these languages shows that such connections exist. The Pashto-Albanian lexical matches were considered above, there are some English-Albanian examples:

Eng beam – Pashto bêna - Alb pemе “a tree”;

Eng blay, Ger Blei – Alb – bli “sturgeon”;

OE borgian, Ger Borg – Alb barga “debt”;

Eng raft, Ger Drift – Alb trap “a raft”;

Eng deer – Alb drё “deer”;

Eng trunk – Alb trung “a stump” (though both can be from Lat truncus);

Some Albanian-Yagnobian matches were found too: Alb hingеllin “to neigh” – Yang hinj'irast «id», Alb anё “bank, shore” – Yagn xani «id», Alb kurriz “back, spine” – Yang gûrk “id”.

The Germanic territory coincides to a great extent with the region of Trzciniec culture of uncertain origin which existed from the second quarter till the end of the 1st mill BC. Thus, this culture can be plausible considered as of Germanic origin. Such assumption may be confirmed by connections of discrete Germanic languages with the Iranians, since the Iranian areas were located near-by on the Dnieper's left banks.